Forensic Experts:

Neal Haskell, PhD: Forensic Entomologist

Posted: March 13, 2023

By: B. Randa

Dr. Neal Haskell is one of the world's leading forensic entomologists, forensic meaning 'of or relating to the investigation of crime' and entomologist meaning 'a person who studies insects.' Despite what the name implies, Dr. Haskell does not investigate crimes committed by bugs – instead, he uses insects as a tool to glean information about human deaths. In fact, Dr. Haskell helped establish the intriguing (albeit stomach-churning) modern field of forensic entomology.

Dr. Haskell did not spend his childhood dreaming about being a forensic entomologist. However, wandering his family's 800-acre farm in Indiana, he often came across animal carcasses and the maggots that inhabited them. In the oddest of love stories, little Neal fell in love with maggots. “Maggots are beautiful,” he's been known to say, proving true the adage that beauty is in the eye of the beholder. And it's not just lip service. His van sports a vanity license plate: MAGGOT.

Dr. Neal Haskell's education

Naturally, Dr. Haskell nurtured his obsession for bugs by achieving an undergraduate degree in entomology in 1969 from nearby Purdue University. After graduating, he returned to his hometown of Rensselaer, Indiana to run the family cattle and soybean farm.

During the 1970s and early 80s, Dr. Haskell worked closely with the county sheriff. Neal Haskell had an interest in firearms (as most rural Midwesterners do), and law enforcement personnel frequented the firing range he built on his farm. Dr. Haskell says he was a special deputy at that time, but it's unclear what Deputy Haskell's duties may have been other than allowing access to his firing range and tagging along with the police. Regardless, this time instilled in him a passion for forensics, and he still remembers the surreal experience of collecting maggots from his first death scene in 1981.

Unfortunately for Farmer Haskell, but fortunately for forensic entomology, Dr. Haskell's livelihood growing soybeans came to an unexpected end. The national farm crisis of the early 1980s acutely affected midwestern farms, and the Haskell farm was not immune. Cattle and soybean farming was no longer viable. In 1984, after consulting with his former professors, Dr. Haskell returned to Purdue University to pursue a master's degree in entomology. He also repurposed his family farm into an 800-acre research laboratory, and his maggot-mania kicked into high gear.

To support the extensive research taking place at his farm, Dr. Haskell needed corpses – lots of them. Luckily, a neighboring farm raised as many as 20,000 pigs per year. Not all those pigs made it to market due to sickness or disease. So, Dr. Haskell had an ample supply of cheap carcasses. And he knew, if you leave them outside, the insects will come.

Entomology's contribution to forensics

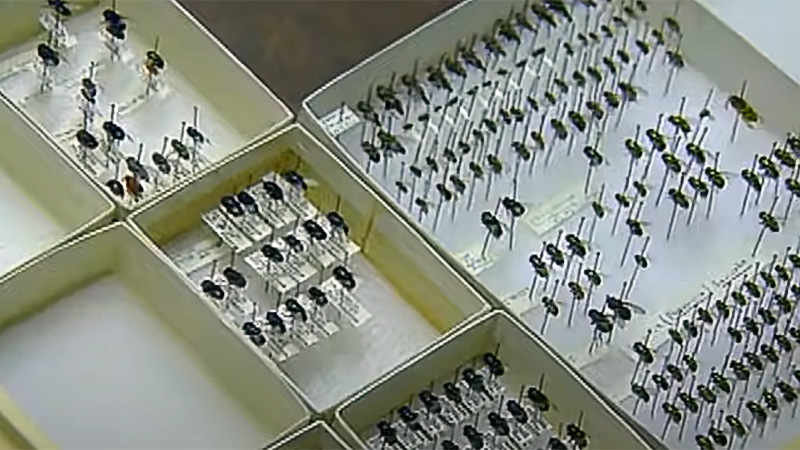

Forensic entomology has a variety of uses. It can be used to determine if a corpse was moved post-mortem and even if drugs were present in the deceased's system at that time of death. But most often, forensic entomology is used to determine the time of death. Blowflies are the most common critters encountered in forensic entomology because they are the first responders of the insect world. Blowflies are drawn to a cadaver and lay their eggs within minutes of death. The predictable lifecycle of the blowfly allows a forensic entomologist to determine a victim's time of death by examining the maturity of the blowflies or their larvae on the corpse.

Crime scene technicians already have a daunting task preserving evidence during a death investigation, and forensic entomology adds another layer of complexity. On top of everything else, thorough crime scene technicians must also find and pluck maggots, other larvae, and insects from the deceased. Dr. Haskell sympathizes with these technicians because his examination and conclusions depend upon the correct evidence being properly collected. To address this concern, Dr. Haskell runs a two-day seminar where attendees receive classroom instruction and actual fieldwork, collecting creepy-crawlies from pig carcasses at his farm.

Ultimately, Dr. Haskell earned his master's degree in entomology in 1989 and later earned his doctorate degree in forensic entomology, both from Purdue University. According to the American Institute of Forensic Education, Dr. Haskell was the first person in the United States to earn those degrees. He is also a board-certified forensic entomologist, of course.

Since 1997, Dr. Haskell has instructed the next generations of forensic entomologists at Saint Joseph's College in Rensselaer, Indiana. Over his career, he has worked over 800 criminal investigations, including the Waco, Texas massacre and the Casey Anthony case. In the latter, he testified for the prosecution – even though their efforts failed to produce a conviction. Dr. Haskell also testifies as an expert witness in criminal and civil trials, and he is known for speaking directly to the jury during examination to keep their attention.

Dr. Haskell followed his dream. He combined his two passions, entomology and forensics, to become one of the most respected professionals in his field. His dream took him around the world, doing what he loves, all while remaining firmly rooted in his hometown of Rensselaer, Indiana.

Find a typo or issue with the details of this article? Leave a comment below, or contact us!

Sources

An article on forensic fingerprinting would not be complete without acknowledging the definitive authority on the subject – The Fingerprint Source Book. This is a publication from the National Institute of Justice, a research, development, and evaluation agency of the U.S. Department of Justice. Much of the information contained in this article was gleaned from this publication which is a great source for more detailed information on forensic fingerprinting.